Museums provide this sacred relation and protected environment, where you feel you are in complete isolation from the rest of the world. One of the main things about my work is that there are possibilities for it beyond those doors, and the museum needs to learn from that experience (Osorio, 2000: 10).

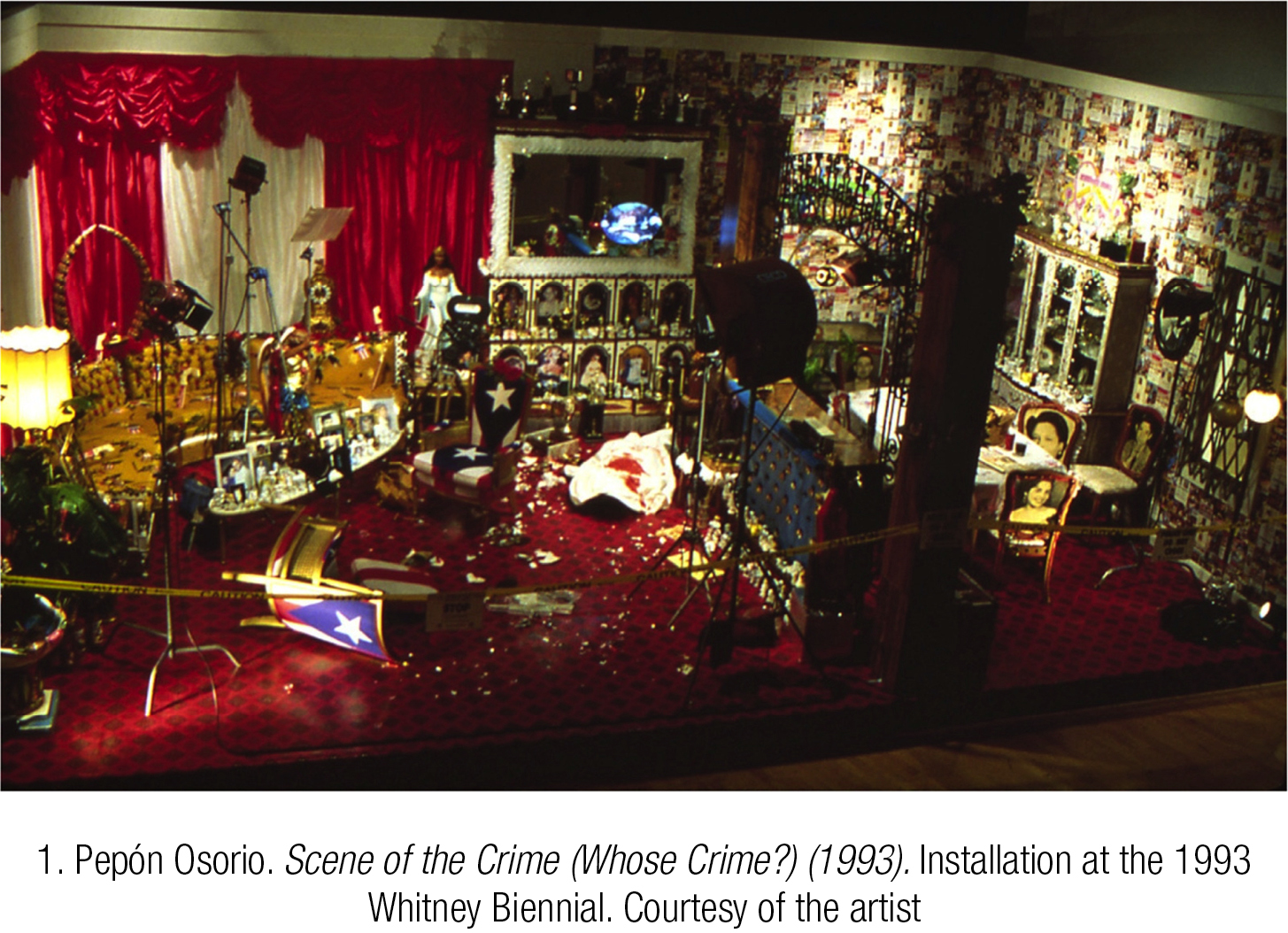

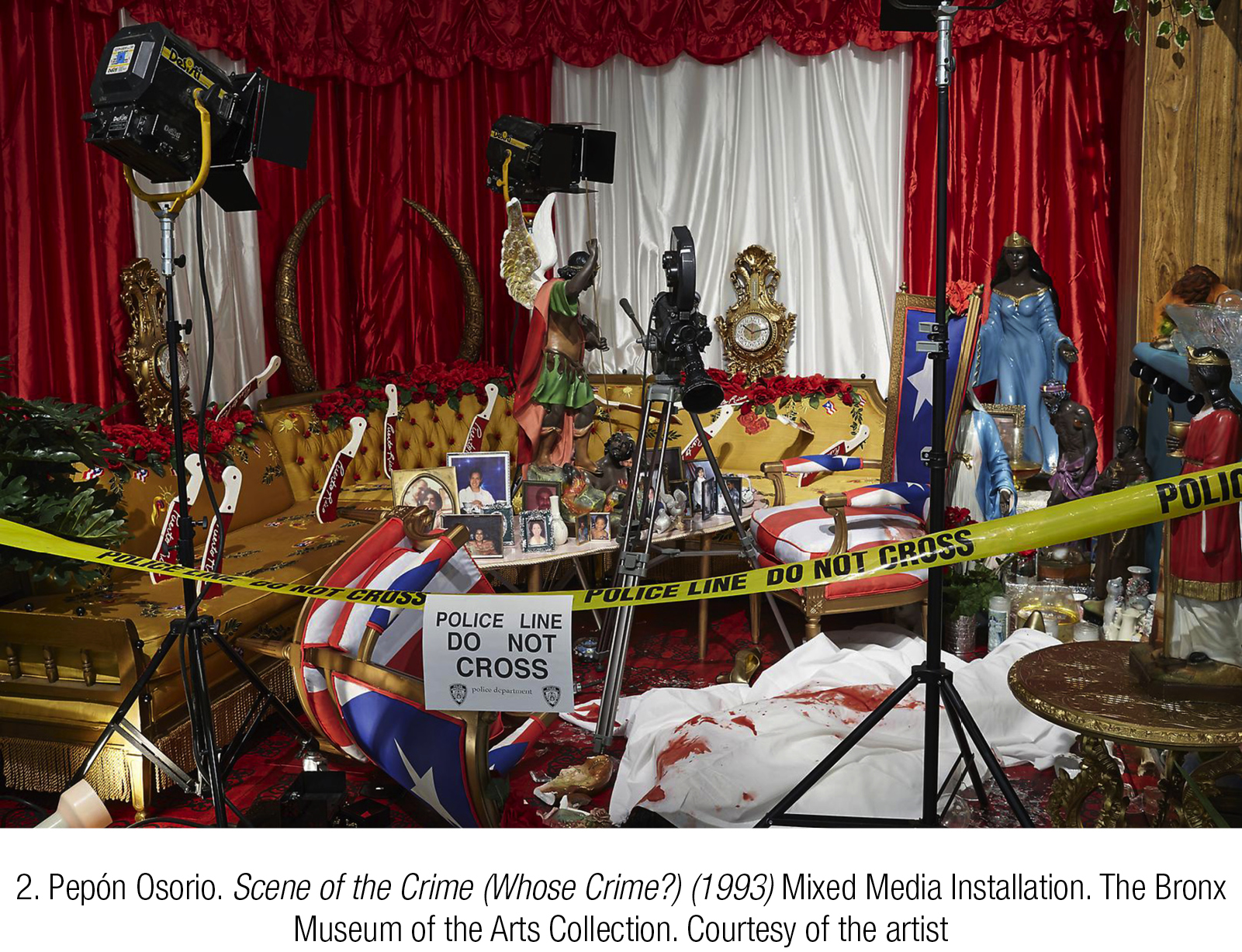

A police line with the instructions «do not cross» delimits the scene of a crime. Everything seems to indicate that this is a case of domestic violence: a woman’s body covered with a bloody sheet lies on the floor of what looks like a Nuyorican apartment. Pieces of glass and china are shattered and scattered everywhere. Chairs upholstered with the Puerto Rican flag are turned upside down. Framed portraits and small figurines of saints made of plastic and porcelain multiply throughout the room. In an adjoining space, a dining room still has the leftovers of breakfast and some newspapers showing headlines about cases of abuse and rape on the table. Hundreds of photographic portraits and advertisements cover all the walls. There doesn’t seem to be a centimeter in the room without some decorative object in it. The colorful horror vacui of imagery, figures, and objects endows the scene with an artificiality that breaks with the realism of the scenography. Nothing would make us think that we are in the confines of a major American art museum.

The author of this staging is the Puerto Rican artist Pepón Osorio, whose installation Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) introduced an interpretation of Nuyorican reality at the 1993 Whitney Museum Biennial. The event, which showed an unprecedented number of works signed by artists of color, went down in the institution’s history as one of the first curatorial proposals that opened up the discourse of contemporary art to include non-white voices1. Most of the artists who exhibited in the Biennial directly confronted the racism implicit in the politics of display of the museum. Pepón Osorio was one of them. By reconstructing in a theatrical manner the interior of a Latino home, the artist abruptly altered the apparently neutral space of the white cube. Osorio’s work, thus, had political implications that questioned, to the point of reverting, the display conventions of the museum and the discourse of contemporary art.

It can be asserted that Osorio’s installation performed a practice that some theorists have agreed to call institutional critique. Indeed, the critical dimension of Osorio’s work is still highly evident today. Nevertheless, I would argue that the effect produced by Osorio’s installation goes beyond institutional critique, as Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) transcended the mere commentary on the museum, implementing a re-reading of the systems of representation and interpretation of Latino culture in the United States. Appealing precisely to his own experience of displacement as a Puerto Rican in New York, Osorio points out not only the discrimination of the Latino and the black community in the art circuits but also the prejudices and stereotypes present in society in general. In what follows, I will try to give an account of the political dimension of Osorio’s installation, concentrating on his particular negotiation of space and his unique use of kitsch. Jennifer A. González has drawn attention to how installation art instigates processes of subjection (2008). Indeed, the overwhelming environment of Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) introduced the museumgoer into a violent situation, challenging the spectator’s modes of perception within the museum. What were the implications of finding the interior of a Nuyorican home in the quasi-sacred framework of the art museum? To what extent did Osorio’s work manage to turn around the modes of interpretation of the artwork?

*

Politics of space shapes modern human life. The places we inhabit contain and convey meaning, influence our social relations and set limits that segregate and exclude. «Our lives are permanently affected through both the writing and organization of space, which are expressions of power» (Kitchin, 1999: 47). The configuration of our cities sets boundaries on the basis of race, ethnicity, or social class, oppressing social groups and communities, and providing cultural signifiers that alert us when we are out of place. In 1993, and still today, a museum of contemporary art like the Whitney Museum carried with it a series of connotations – high culture, exclusivity – that made it an inaccessible place for a large part of the New York population.

Osorio was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico, and moved to New York at the age of 20. His own experience as a black Puerto Rican living in the city was affected by these political boundaries imposed by socio-spatial organization2. Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) deals precisely with ideological and cultural barriers imposed on the space we inhabit and occupy. Not surprisingly, Osorio’s work for the 1993 Whitney Biennial operated in a spatial way. By placing a subaltern domesticity in the neutral setting of the museum, the installation introduced the beholder into a liminal space where conflicting structures of power met (González, 2008). By means of spatial disruption, his work put opposing realities – that of the museum/art realm and that of the street – into a conversation.

In an interview with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Osorio openly manifested his discontentment with the institution of the museum, expressing a desire to move away from dominant modes of representation (2000: 6). Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) seems to respond to this discontent, given that its scenography sought precisely to accentuate a sense of strangeness within the setting of the museum. Some years before his piece was shown, Osorio recognized that «the experience implicit in museum and gallery exhibition has not been one to which Puerto Rican people have been historically welcomed, specifically for the contextualization of their culture» (1991: 24). Staging the interior of a home in the museum space, Osorio’s work appropriated the diorama display, commonly used by the colonial ethnographic museum to depict an exotic and folkloric image of non-western societies.

In 1992 Gerardo Mosquera introduced the concept of Marco Polo’s syndrome to describe the postmodernist attraction of the centers towards otherness, which allowed a greater circulation and legitimization of art of the peripheries. However, Mosquera alerted that

too frequently, value had been placed on art that explicitly manifested difference, or better satisfied the otherness expectations of postmodern neo-exoticism. […] As a consequence, this attitude would have stimulated the self-othering of the peripheries, where some artists – consciously or unconsciously – had inclined towards a paradoxical self-exoticism (2001: 30-31, emphasis in original).

Similarly, Kobena Mercer has spoken of a «burden of representation» to allude to how non-Western artists are presupposed to stand as representatives or to «speak for» their cultural community to satisfy the mainstream discourse of art (1990). I would argue that in Osorio’s case, the artist consciously undertook a self-exoticization in an explicitly critical way, appropriating the ethnographic museum’s discourse to precisely denounce its racist connotations. In the words of Chon A. Noriega,

Rather than representing a community, Osorio’s installations offer an opportunity for unplanned discourse and reciprocity across communities. The installations are symbolic representations of institutional and social relations – relations founded across the thresholds of defined spaces (2013).

Through the decorative exaggeration and the excess of objects of his scenography, Osorio appropriated the stereotype of the Latino in order to underscore the racism implicit politics of display of the museum.

Osorio’s piece resonates with some institutional critique practices developed by other artists in the 90s that explicitly confronted questions of identity and racial politics within the museum. A case in point is Fred Wilson’s intervention at the Maryland Historical Society in 1992, Mining the Museum, in which the artist reorganized the museum’s collection to draw attention to United States’ slavery history. Both artists belong to a generation of racialized artists who employed installation in the early 90s to render explicit the structural racist ideology of the art institution. Yet, in contrast to Wilson’s work, Osorio’s institutional critique does not rely on the very exercise of museology to criticize its racist tendencies. Or, at least, his appropriation of the display models is developed differently. While Wilson’s intervention uses an aesthetic expression typical of the museum, Osorio bursts into space with a scenography completely alien to the white cube. His intervention is not camouflaged within the museum’s collection, rather, it disturbs, it strikes, it shocks. As such, the visual effect of Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) in the aseptic space of the museum is completely disruptive. Osorio’s complex staging achieved a total loss of Benjamin’s aura, posing a new form of relationship between the artwork and the public (Benítez, 2000: 16). As a result, «the viewer [occupied] a liminal position with respect to the scene, negotiating her or his space through the give and take of the objects» (Indych, 2001: 19). The excessive theatricality of the installation absorbed the beholder, who, for a few moments, was taken away from the space of the gallery. The outcome was a shock: the spectator –the privileged– experienced the obstacles that the rest of the people usually have to cope with when being in the museum. Now it was the museumgoer who felt out of place.

If we consider the paradigm of relational aesthetics put forward by the theorist and critic Nicolas Bourriaud (2002), we can better grasp the idea of spectatorship proposed by Osorio’s work. As suggested by the theorist, during the decade of the 90s, a turn towards a common aesthetic based on encounter and experience arose in the artistic field. Consequently, according to Bourriaud, «it is no longer possible to regard the contemporary work as a space to be walked through» (2002: 15), since works from this decade were increasingly conceived as experiences, as durations to be lived, «like an opening to unlimited discussion» (15). Artworks would therefore constitute relational objects, setting up «relations between individuals and groups, between the artist and the world and, by the way of transitivity3, between the beholder and the world» (26). Although Osorio’s installation was not conceived in a participatory manner, this conception of transitivity manifests through the centrality of the experience of the beholder in the aesthetic apprehension of the work, an experience that it is presented as a period of time to be lived through.

By means of this novel notion of spectatorship that combined a new sense of space and time, Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) introduced a different reality into the museum. This new reality might seem uncomfortable for the common museumgoer, who took the position of a voyeur that witnessed someone else’s privacy: through the transitivity of which Bourriaud speaks, the spectator’s gaze became then part of the work itself and not just a binding medium. The strangeness provoked by Osorio’s domestic scene was further increased by the introduction of the corpse and the glass fragments, which accounted for an extremely violent act. The question that gives the installation its title, «Whose Crime?» echoed in the minds of viewers, whose sense of reality was challenged. The observer’s experience revolved around the negotiation between these two spaces: that of the museum and that of someone else’s home. Commenting on the work’s negotiation of space, Osorio observed that

When this piece, Scene of the Crime, was at the Whitney Museum, it almost felt as if I had taken a piece of the South Bronx out of its roots and placed it in the middle of Madison Avenue, you know? And that’s my relation to space. That’s my relation –one of intervening, of intervention– one of somehow juxtaposition, but at the same time trying to fit in or force it into a location, more than anything else. And maybe that’s how I feel with my work, that it goes against the grain. But somehow, because of its spiritual qualities, it flows in itself (2019).

It is no surprise that Osorio has often cataloged his artistic practice as a sort of squatting into the museum. By introducing a piece of lower-class Nuyorican reality into the exhibition space, the installation «captivated viewers drawing them into large and complex social frameworks wherein the self and the other do not have the comfort of distance through difference» (Noriega, 2013). The strategy employed by the artist to create these social frameworks is exaggeration.

The visual excess of Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) was achieved by a use of kitsch that fluctuated between the nostalgic or identitarian, and the parody. Osorio’s kitsch aesthetics draw from his engagement with Puerto Rican popular culture during his childhood on the island, but also throughout his experience working with Puerto Rican communities in New York City. The accumulation of porcelains, plastic figurines, leopard patterns, and artificial flowers granted Osorio’s domestic space with a theatrical character that enclosed multiple layers of meaning. As Kellie Jones suggests,

[…] his abundance parodies a world where people of color often lack the basics of health care, education, and money. In place of denial and poverty, the artist invents a universe where more is indeed more, as opposed to the contemporary «less is more», and more is better (1991: 31).

Hence, the political intent intrinsic to the use of kitsch takes on multiple implications. Exploiting that maxim of «more is more, and more is better» within the minimalist space of the contemporary art museum, Osorio directly problematized the normative opposition between high and low culture, challenging what is considered acceptable for the museum and what is not. Osorio introduced into his installation objects that diverged from the exhibition logic inherent in the artistic discourse – most evident when we take into account the prominence of the minimalist movement in American artistic modernity. The inclination towards a kitsch language was the response of Osorio’s interest in maximizing subaltern elements within all the layers of his artistic proposal. For the artist, these objects would perform as a metaphor of the social classes and groups traditionally excluded from the museum, destabilizing the hegemonic discourse of contemporary art and calling into question the conventional systems of visibility that operate within the institutional realm, since «[museums] divide the field of material culture into legitimate culture and illegitimate culture – or rather, nonculture, to the extent that the illegitimate is denied a representative function in the public sphere framed by institutions» (Fraser, 2011: 321).

Yet Osorio’s kitsch style was not limited to playing with the notions of good/bad taste or high art/popular culture to dismantle the exclusionary institutional dispositif. It also dealt with the contradictions of Puerto Rican identity itself. In many of his installations, Osorio focuses his criticism on the veneration of Puerto Rican society to elitist models of their Spanish roots that relegates to a second spot other popular traditions, especially those with African origins (Jones, 1991: 31). His use of catholic imagery could be identified with what Celeste Olalquiaga has called a third-degree of Kitsch:

Besides imploding the boundaries of art and reality, the third degree of kitsch carries about an active transformation of kitsch. Taking religious imagery both for its kitsch value and its signifying and iconic strength, it absorbs the icon in full and recycles in into new meanings (1996: 284).

Thus, the presence of religious motifs in the installation offers multiple readings and contains meanings not first apparent to the naked eye. The inclusion of seven large saint figures seems to reference Santería, a syncretic religion of African (Yoruba) and European (Catholic) traditions practiced in the Americas and the Caribbean4. As Jennifer González has suggested, Osorio’s subtle allusions to Santería should be understood as a subtext within the larger visual argument (2008: 175-177). Latin American interest in visual excess has been often discussed by scholars as a result of its historical circumstances. Some have traced the origin of kitsch aesthetics in the objects created by mestizo artists in seventeenth and eighteenth-century New Spain (Indych, 2001). As Coco Fusco argues, «Latin American hosts a variety of popular and high-art traditions in which kitsch is deployed self-consciously as a gesture of cultural resistance» (1995: 90). Osorio’s kitsch aesthetic deftly combines a sharp insight into Puerto Rico’s colonial history with personal recollections of his boyhood on the island, yet it also responds at his own experience as a black Latin American in New York dealing with feelings of exclusion and non-belonging. His fantastic recreation of a Nuyorican home took exaggeration and excess to its ultimate consequences. On the one hand, it could be said that the construction of this kitsch universe could respond to the idea of the Puerto Rican home as a place of self-expression and nostalgic escape for those exiled in a city like New York, since, as Olalquiaga has suggested, kitsch results from the commodification of the souvenir, hence it functions as a way to hold down and fix memories and emotions (1998). Yet it is also interesting how through the tacky style and the introduction of violence in the scene, the work, in a sort of détournement, added another layer of intelligibility to its interpretation.

Kitsch aesthetics and violence are two of the stereotypes with which American society often identifies Latinos. In Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) Osorio specifically appealed to the presence of these stereotypes in mainstream American media. By placing a film camera in his scene, the installation became a melodrama movie set. The mat that welcomed the public to the installation conveyed an appalling message: «Only if you can understand that it has taken years of pain to gather into our homes our most valuable possessions; but the greater pain is to see how in the movies others make fun of the way we live». Osorio addressed the spectators directly, making them interrogate themselves about the representation of his community in the American cultural imaginary. In one section of his installation, the allusion became even more literal, as he introduced boxes of VHS videotapes that perpetuated Latin stereotypes confronted with phrases taken from interviews he conducted within Latin American communities. The body on the floor, which paradoxically had become secondary considering the overwhelming cluster of objects in which it was immersed, also represented the scene of a larger social crime: that perpetuated by contemporary society through racism and stereotyping (González, 2008: 177). The dead body was the emblem of Puerto Rican culture as a whole. As Liliana Ramos claims, «this is the ancestral victim, the perpetual victim: the Other» (2000: 76).

The brutality with which Osorio disrupted the white cube and addressed the viewer with his overwhelming environment seemed to be too much for some visitors. As Elisabeth Sussman – one of the curators of the exhibition – recalls, the Whitney Biennial of 1993 seemed to «offend everyone» (2005: 76)5. Indeed, the show came up against a torrent of negative criticism, which reiterated the idea of «political correctness» by implying that quality had been sacrificed in favor of inclusion and multiculturalism. «There are over 150 items by eighty-odd hands in the 1993 Biennial» – Roger Kimball explained in a review for The New Criterion – «none, not one, is a work of art except in the technical sense that it has appeared exhibited as such in a gallery or museum» (1993: 54). Like him, many others deplored the quality of the proposal. Perhaps, as Luis Camnitzer later expressed, «Since there are plenty of enemies around, a successful Biennial would have constituted a regrettable political defeat» (1993: 129-130). Certainly, one of the most relevant critical reflections on the exhibition was the one published by October in the Fall of 1993, which brought into a conversation Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Silvia Kolbowski, Miwon Kwon, and Benjamin Buchloh. Throughout the discussion, Hal Foster reflected on how the political urgency of the works

[deflected] from full attention to work on the work, to work on its materials and forms, not in the sense of formalism but in the sense of signification: how materials signify, in what ways meanings are informed historically and delimited institutionally (1993: 4).

Yet I would suggest that, in the case of Osorio’s work, the political message would be drawn precisely through the multiplicity of readings offered by the countless signifiers it presented. As I have previously argued, the work operated through overlapping layers of meaning, revealing the very complexity of the artist’s identity, and performing a thorough re-examination of the conventions of the museum’s display politics. Concerning diasporic artistic practices, Kobena Mercer has pointed out that

[…] because all systems of signification are socially shared among dominant and subaltern identities, what matters most are the inflections and accentuations by which signifiers get lifted out of established codes in acts of appropriation that dispute what is accepted as reality (2016: 15).

This very idea lies at the core of Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?), as it negotiates the notion of Latino as a constructive semiotic field, challenging the segregating ontologies present in American collective imaginary6.

*

Osorio’s Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) was the result of the artist’s own sense of strangeness in the museum. For Osorio, the institution of art constitutes a dispositif where the dominant white gaze legitimizes a series of power relations –where the other is never accepted. When, in 1993, the artist had the opportunity to enter a major American museum, instead of adapting his work to the needs of the space –or rather, to the needs of the (quite likely white, high-class, privileged) visitors’ perspective–, he subverted both space and spectatorship dynamics. He did so through the strategies described above: negotiating with spatiality, as he managed to introduce the private space of the subaltern home into the realm of the museum, materializing a metaphor of the society that is usually excluded from the field of high art. Osorio’s installation raised an imaginary but very explicit frontier between the world it represented and the space where it was being represented. Undermining the excluding discourse of the museum and the stereotyped and exoticizing perception of museumgoers towards Latinos, Osorio’s scene used kitsch as a second strategy to emphasize the idea of strangeness. Through kitsch, the artist arranged a cosmography completely alien for the museum’s visitors, yet, paradoxically, valid for their criteria, insofar as it represented their assumed ideas of the Latino community. In this way, Osorio overcame the «burden of representation» by appropriating the exotic perception of Otherness, subverting the reading of the kitsch, and directly pointing to the racism present in the media and in cultural narratives.

Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) succeeded in generating a disruption because the work was a statement of Osorio’s feeling as a stranger in the museum and in American Society. Indeed, it could be asserted that the mainstream museum was not the right space for him: nor for his type of art, nor for his sociological view of the world. The interesting aspect about Osorio’s intervention in the Whitney Biennial was that, with the violence of the scene and the multiplicity of symbols, the artist seemed to scream to the public: «I shouldn’t be here!» or, more specifically: «You’re not prepared to understand me in my individual and collective complexity. Do you want a cliché? Here it is.» Consequently, the discomfort that would normally be experienced by low-class black Puerto Ricans in a space like a museum was then transferred to the privileged museumgoers.

Not surprisingly, Osorio’s next works would take place outside the perimeter of the museum. Intending to reach an excluded audience, his installations began to develop a more evident social dimension, as he carried out public art projects aimed at bringing art to those spaces that had traditionally been excluded from the artistic institutional realm. This transformation can be noted in some of the works that followed the Whitney Biennial, such as En la barbería no se llora (No Crying Allowed in the Babershop) (1994), which was located in a barbershop in Connecticut and addressed the issue of masculinity and homophobia; or Badge of Honor (1995), a work resultant from the artist’s engagement with Newark’s Puerto Rican community that focused on the separation of a father and a son by incarceration. More recently, the artist has developed collaborative initiatives more decidedly social, such as reForm project (2014-2016), which emerged in response to the shutdown of Fairhill Elementary School in North Philadelphia, and took place as an installation and a series of workshops involving a group of teachers, students, and neighbors. As such, his latest practice in the public space can be situated in the framework of what Miwon Kwon has come to call «collective artistic praxis» (2002: 154), as it avoids the notion of community representation and proposes spaces for interaction and discussion, always maintaining a critical approach to racial and class stereotypes.